The Water Paradox: When Mismanagement Matters More Than Scarcity

The Water Paradox: When Mismanagement Matters More Than Scarcity

Edward B. Barbier makes the definitive economic case that the global water crisis is not about running out of water — it is about failing to manage what we have. A review of The Water Paradox: Overcoming the Global Crisis in Water Management.

A Question That Haunts the Industry

Edward Barbier opens The Water Paradox with a question that deserves to be pinned to the wall of every utility boardroom on the planet: if water is so valuable and increasingly scarce, why is it so consistently mismanaged?

It is a deceptively simple question. Barbier’s answer — spanning millennia of human history, dozens of national case studies, and rigorous economic analysis — is neither simple nor comfortable. The global water crisis, he argues, is not primarily a crisis of scarcity. It is a crisis of management. Outdated governance structures, persistent underpricing, and misaligned incentives have created a vicious cycle in which water is simultaneously the most essential resource on earth and the most poorly administered.

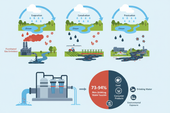

The numbers validate his thesis. As of August 2025, WHO and UNICEF data confirm that 2.1 billion people — one in four globally — still lack access to safely managed drinking water. The World Bank’s landmark 2025 Global Water Monitoring Report found that the planet loses 324 billion cubic meters of freshwater annually, enough to supply 280 million people, driven overwhelmingly by poor management practices rather than absolute physical shortage. In the United States, Bluefield Research reported that nearly one in five gallons of treated drinking water — 19.5% — is lost before reaching customers, costing utilities more than $6.4 billion in uncaptured revenue every year.

The Vicious Cycle at the Heart of the Book

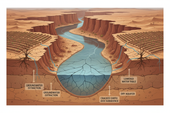

Barbier, a professor of economics and senior scholar at Colorado State University’s School of Global Environmental Sustainability, structures his argument around what he calls a “vicious cycle” of water mismanagement. The mechanism is straightforward: outdated governance structures and persistent underpricing of water lead to overuse and environmental degradation. This intensifies scarcity, which triggers reactive crisis spending on expensive infrastructure rather than systematic reform of the institutions and incentives that created the problem in the first place.

The water crisis is as much a failure of water management as it is a result of scarcity. Outdated governance structures and institutions, combined with continual underpricing, have perpetuated the overuse and undervaluation of water.

This cycle is visible at every scale. It is the pattern behind a city spending hundreds of millions on a new treatment plant while its distribution system loses 30–40% of treated water through leaks. It is the pattern behind agricultural subsidies that incentivize water-intensive crops in arid regions while aquifers beneath those farms are irreversibly depleted. And it is the pattern behind national water policies that respond to drought with emergency spending rather than institutional reform.

Barbier documents this cycle across civilizations and centuries, building a case that is both historically sweeping and empirically grounded. A particularly striking detail: in 2017, Rome’s fountains — engineering marvels that had operated continuously for two thousand years — were turned off for the first time due to drought. A civilization that perfected hydraulic engineering nevertheless found itself unable to manage the resource those systems were designed to deliver.

Three Pillars of Reform

The second half of The Water Paradox — which Barbier himself acknowledges is where the real value lies — lays out a comprehensive reform agenda organized around three interconnected pillars.

1. Reforming Governance and Institutions

Barbier argues that water governance remains fragmented in most countries, divided along political boundaries rather than managed by watershed or river basin. The result is a patchwork of overlapping jurisdictions, competing priorities, and institutional silos that prevent coordinated management.

He highlights jurisdictions that have moved toward integrated river basin management — notably Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin and parts of Canada — as models that demonstrate significantly better outcomes in monitoring, allocation, and long-term sustainability. These are not theoretical proposals. They are functioning systems that have measurably outperformed the fragmented alternatives.

Water management fragmented by political boundaries rather than hydrological basins creates institutional silos that guarantee coordination failure. Jurisdictions that have adopted basin-scale integrated management consistently achieve superior outcomes — not through better technology, but through better organizational design.

2. Ending the Underpricing of Water

Barbier’s most politically charged argument — and arguably his most important — is that water is chronically underpriced worldwide. He proposes a two-component pricing structure: a fixed charge for all users to cover the full operational costs of the system, and a tiered volumetric rate where higher consumption means higher per-unit costs. He further argues that agricultural irrigation subsidies, which represent the largest share of global water consumption, should be phased out.

The evidence he assembles is compelling. Efficient pricing has historically done more to promote conservation and manage demand than regulatory restrictions or mandated water-saving technologies. This finding has significant implications: it suggests that properly structured market mechanisms can achieve sustained behavioral change across millions of individual water users — something command-and-control regulation often struggles to accomplish.

Barbier acknowledges that pricing reform is politically difficult. He also demonstrates that the alternative — continued underpricing — is economically devastating. When water is priced below its true cost, utilities cannot generate the revenue needed to maintain infrastructure, invest in loss reduction, or fund the systematic improvements that prevent catastrophic failures. The $6.4 billion in annual U.S. non-revenue water losses is a direct consequence of pricing structures that fail to signal the real value of treated water.

Underpricing water does not make it more affordable — it makes it less reliable. When prices fail to cover operational costs, the resulting infrastructure decay and service degradation fall hardest on low-income communities who have the fewest alternatives. Barbier’s tiered pricing proposal protects affordability for essential use while signaling the true cost of excessive consumption.

3. Supporting Innovation

Barbier completes his reform framework by arguing that current pricing and governance failures actively suppress innovation. When water is essentially free or deeply subsidized, there is no market incentive to develop water-saving technologies, more efficient irrigation systems, or smarter distribution networks. Innovation requires economic signals that reward efficiency — and those signals are systematically absent from most water markets.

This is a particularly important argument because it reframes the technology debate. The water industry frequently discusses technology adoption as though it were primarily a procurement challenge: buy the right sensors, install the right software, deploy the right meters. Barbier shows that technology adoption is fundamentally an economic challenge. Without price signals that make water efficiency profitable, even transformative technologies will be underadopted or underutilized.

Technology investment without institutional and economic reform produces diminishing returns. Barbier demonstrates that innovation follows incentives: when water is properly priced and governance systems reward efficiency, technology adoption accelerates naturally. When these conditions are absent, even the best technology underperforms.

Global Scope: From the Murray-Darling to Water Grabbing

One of the book’s great strengths is its geographic breadth. Barbier draws on case studies from every continent, weaving together evidence from ancient civilizations, developing nations, and wealthy OECD economies to demonstrate that the water paradox is genuinely universal.

His treatment of the Murray-Darling Basin provides a valuable case study in what integrated management can achieve when governance structures align with hydrological reality. Australia’s experience — including both the successes of cap-and-trade water markets and the political controversies they generated — offers practical lessons for any jurisdiction contemplating governance reform.

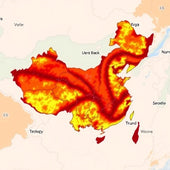

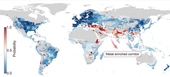

Barbier also documents the rise of “water grabbing” — the practice of nations and corporations acquiring water rights in other countries, often in developing regions — as a direct consequence of governance failure. When domestic water management institutions fail, the resource becomes a target for external appropriation, deepening inequality and creating new sources of geopolitical conflict. He identifies both the top water-grabbing countries and the most vulnerable target nations, mapping a pattern of resource extraction that follows predictably from institutional weakness.

The book’s global scope also reveals a striking pattern: the same management failures recur across vastly different economic and political contexts. Whether examining groundwater depletion in India, infrastructure decay in the United States, or transboundary river disputes in Central Asia, the underlying dynamic is the same — underpricing, fragmented governance, and suppressed innovation producing predictable and preventable failures.

The Limits of the Economic Lens

The Water Paradox is primarily an economist’s book, and that is both its strength and its limitation. Barbier excels at diagnosing systemic market and governance failures at the national and international level. His command of global data is impressive, and his policy prescriptions are economically rigorous.

However, the book gives less attention to the operational mechanics of how individual utilities can implement the reforms he advocates. Pricing reform is discussed at the policy level, but the practical challenges of meter deployment, billing system modernization, customer communication strategies, and operational workflow redesign — the work that determines whether pricing reform succeeds or fails at the point of delivery — receive relatively brief treatment.

Similarly, Barbier’s discussion of innovation focuses primarily on research and development incentives rather than on the day-to-day operational processes — standard operating procedures, preventive maintenance schedules, staff training protocols, performance benchmarking — that determine whether new technologies deliver their promised benefits once installed. A utility can purchase the most advanced leak detection system on the market, but without the operational protocols to act on the data that system generates, the investment will underperform.

This is not so much a criticism as an identification of where Barbier’s macroeconomic framework invites complementary analysis. He provides the diagnosis of what needs to change at the system level. The question of how to make those changes work at the utility level — where the water actually reaches customers — remains the operational challenge for the sector to solve.

The Financial Case for Institutional Reform

Barbier’s analysis, combined with the latest industry data, builds a financial case that is difficult to dismiss:

The scale of waste is enormous. Global non-revenue water totals an estimated 346 million cubic meters per day, according to the International Water Association. In developing countries, the World Bank estimates NRW frequently exceeds 50% of total production. The economic cost of water management failure runs into the hundreds of billions annually.

Reactive infrastructure spending is not a solution. With U.S. water mains breaking approximately every two minutes across a 2.2-million-mile distribution network, the capital expenditure required for pipe-by-pipe replacement is staggering. Barbier argues persuasively that infrastructure investment without institutional reform simply perpetuates the vicious cycle — new pipes installed into the same dysfunctional governance and pricing systems will degrade along the same trajectory.

Institutional reform unlocks investment returns. Barbier’s pricing proposals would generate the revenue streams needed to sustain infrastructure investment over time. Full cost recovery pricing, combined with governance reform that enables coordinated management, creates the institutional conditions under which both capital investment and technology adoption deliver their maximum potential returns.

The Verdict

The Water Paradox is one of the most important books published on water management in the last decade. Barbier’s central insight — that our water crisis is fundamentally a management crisis — is not new, but no one has assembled the global evidence more comprehensively or argued the case more persuasively. His three-pillar reform framework (governance, pricing, innovation) provides a coherent and actionable structure for thinking about systemic change.

For utility leaders, the book offers essential context: it explains why individual utilities struggle with the challenges they face by locating those challenges within a global pattern of institutional failure. For regulators and policymakers, it provides an evidence-based roadmap for reforms that have worked in comparable jurisdictions. For financial professionals, it quantifies the economic cost of inaction and the returns available from institutional reform.

The book’s primary gap — limited attention to utility-level operational implementation — is an invitation rather than a flaw. Barbier gives us the systemic diagnosis. The operational question of how to translate that diagnosis into day-to-day utility practice remains the sector’s central challenge, and its greatest opportunity.

Book Details

- Title

- The Water Paradox: Overcoming the Global Crisis in Water Management

- Author

- Edward B. Barbier

- Publisher

- Yale University Press, 2019

- Pages

- 281

- ISBN

- 978-0-300-22443-6

- Rating

-

★★★★☆

Essential macro-level analysis of why water management fails globally; pair with operational frameworks for complete utility application.

This review is published by E-Score Water (escorewater.org) as part of the Books blog series. E-Score Water maintains editorial independence and has no commercial relationship with the publisher or author.