Beyond Borders: Why Africa's Water Security Crisis Demands Operational Excellence

At the Atlantic Dialogues in Rabat this week, African officials delivered stark assessments of how water scarcity is driving food insecurity, regional conflict, and migration across the continent. Ibrahim Mayaki, the African Union's Special Envoy for Food Systems, presented the challenge in uncompromising terms: with 90% of Africa's surface water and 40% of groundwater shared across borders, strictly national approaches to water management fundamentally 'reduce the space of the solution.' Yet buried in Mayaki's presentation of obstacles was a critical admission that transcends the diplomatic focus on transboundary cooperation: the continent faces 'inadequate technical systems to manage and distribute water locally.'

This identification of weak local operational capacity reveals why Africa's water crisis persists despite decades of investment in water infrastructure. The problem isn't primarily about cooperation frameworks or political will—though both matter. The fundamental issue is that African water utilities and management agencies lack the operational protocols that would make expensive infrastructure investments actually deliver consistent performance.

The Operational Gap Behind the Headlines

Mayaki identified three major obstacles to effective water management: political resistance rooted in national interests, weak or incomplete data on water volumes, and inadequate technical systems to manage and distribute water locally. The diplomatic discussions naturally focused on the first obstacle—getting countries to cooperate across borders. But the third obstacle reveals the operational reality undermining even successful cooperation agreements.

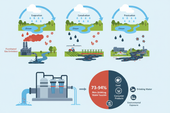

Consider what 'inadequate technical systems to manage and distribute water locally' actually means in practice. It means water utilities receiving funding for treatment plants and distribution networks but lacking standardized operating procedures for running them consistently. It means operators making critical decisions based on individual judgment rather than documented protocols. It means maintenance happening reactively when systems fail rather than systematically before problems occur. It means data collection systems that produce unreliable information because data quality protocols don't exist.

This operational gap explains why Mayaki also listed 'weak or incomplete data on water volumes' as a separate obstacle. The data problem isn't primarily about lack of monitoring equipment—though that matters. The fundamental issue is that utilities lack the operational systems that would generate reliable data systematically. You cannot produce accurate water volume data without standardized measurement protocols, systematic calibration procedures, and quality control frameworks. The data weakness is a symptom of operational inadequacy.

From Diplomatic Agreements to Operational Reality

Former Gambian Foreign Minister Mamadou Tangara highlighted successful cooperation between Gambia and Senegal on shared water bodies, describing it as effective preventive diplomacy. This cooperation matters—transboundary water management requires functional diplomatic frameworks. But here's the uncomfortable reality: even the most sophisticated cooperation agreement cannot compensate for weak operational capacity at the local utility level.

When countries agree to share water resources equitably, that agreement only delivers results if the utilities managing those resources can actually operate their systems consistently. If a utility lacks standardized procedures for treatment optimization, systematic maintenance protocols, and reliable data collection systems, then its portion of shared water resources will be managed inefficiently regardless of how well the diplomatic framework functions. Cooperation agreements establish what should happen. Operational excellence determines what actually happens.

The Security Implications of Operational Failure

Tangara's warnings about security consequences make the operational excellence imperative even more urgent. He described how the shrinking Lake Chad Basin contributed to the rise of Boko Haram, and how overfishing by foreign fleets pushed young coastal Africans toward irregular migration—'instead of building boats to go and fish, they build boats to cross the Atlantic.' These security and migration pressures stem from resource scarcity and livelihood collapse.

But resource scarcity isn't just about absolute water availability. It's also about how effectively available water is managed. A utility with strong operational protocols can deliver reliable water service to more people with less water than a poorly managed utility with abundant resources. In contexts where water stress is driving conflict and migration, the difference between operational excellence and operational mediocrity isn't just about service quality—it's about regional stability.

Tangara's example of Cape Town's dam capacity swinging from 6% one year to flooding the next illustrates this dynamic. Climate variability creates operational challenges, but operational protocols determine whether systems can respond effectively. Cape Town's Day Zero crisis resulted not just from drought but from inadequate operational systems for demand management, leak detection, and water use optimization. When the rains returned, the lack of systematic protocols for managing reservoir levels and controlled releases contributed to flooding risks.

The Population-Infrastructure-Operations Triangle

Mayaki noted that Africa's population grew from 300 million in the 1960s to nearly 1.5 billion today, with urbanization intensifying pressure on water systems. He observed that governments underestimated demographic growth, leaving countries with no choice but to accelerate reforms. The conventional response to this pressure focuses on infrastructure expansion—build more treatment plants, extend more pipelines, drill more boreholes.

Yet infrastructure expansion without operational excellence creates a vicious cycle. New facilities are built and immediately underperform because utilities lack the operational protocols to run them effectively. This underperformance creates pressure for even more infrastructure investment, which utilities again cannot operate at design capacity. The result is countries investing heavily in water infrastructure that never delivers its potential performance because the operational systems needed to make infrastructure work effectively are systematically underfunded.

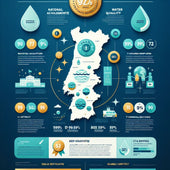

The utilities achieving exceptional performance globally have broken this cycle by recognizing that operational protocols aren't separate from infrastructure—they're what make infrastructure valuable. Singapore's Public Utilities Board manages water for 5.7 million people with one of the world's most efficient systems not because it has unlimited infrastructure but because it operates its infrastructure with systematic protocols for optimization, maintenance, and continuous improvement. Portugal's Águas do Algarve serves 450,000 people with 99.95% microbiological compliance not through revolutionary technology but through rigorous implementation of WHO Water Safety Plan protocols.

What This Means for African Water Management

Mayaki's frank assessment that Africa faces 'inadequate technical systems to manage and distribute water locally' demands a fundamental shift in how water investments are evaluated and funded:

-

Infrastructure projects should include mandatory operational protocol development. When funders approve a treatment plant expansion, they should require utilities to demonstrate standardized operating procedures, systematic maintenance protocols, and data quality frameworks before disbursing funds. Infrastructure without operational systems is just expensive underperformance.

-

Data system investments must prioritize operational protocols over monitoring equipment. The weakness in water volume data stems from lack of systematic measurement and quality control procedures, not primarily from lack of sensors. Utilities need protocols for calibration, verification, and data validation before additional monitoring equipment will produce reliable information.

-

Regional cooperation frameworks should include operational capacity building. Transboundary water agreements establish what countries should do with shared resources. But these agreements only deliver results when utilities can actually operate their systems effectively. Regional institutions should invest as heavily in operational protocol development as they do in diplomatic coordination.

-

Climate adaptation must focus on operational resilience, not just infrastructure expansion. Tangara's Cape Town example shows that climate variability creates operational challenges that systematic protocols can address. Utilities need standardized procedures for demand management during scarcity and controlled operations during abundance. Infrastructure alone cannot provide climate resilience.

Beyond the Summit

The Atlantic Dialogues discussion correctly identified water security as central to Africa's stability, food security, and migration pressures. The diplomatic focus on transboundary cooperation addresses real challenges. But Mayaki's identification of 'inadequate technical systems to manage and distribute water locally' reveals the operational reality that undermines even successful cooperation agreements.

African countries can establish sophisticated frameworks for sharing transboundary water resources. Development banks can finance ambitious infrastructure expansion. Regional institutions can coordinate climate adaptation strategies. But none of this delivers results unless utilities develop the operational protocols that make infrastructure actually perform consistently.

The security implications make this imperative urgent. When water scarcity drives conflict and migration, operational excellence isn't just about service quality—it's about whether communities can sustain livelihoods despite climate stress. The choice for African water utilities is stark: invest in operational protocols that make infrastructure perform effectively, or watch expensive infrastructure investments fail to prevent the security consequences that inadequate water management creates.

The utilities achieving exceptional performance globally have already demonstrated that operational excellence is achievable even in challenging contexts. The question for Africa: will water investments continue to prioritize infrastructure over the operational systems that make infrastructure valuable, or will Mayaki's frank assessment of 'inadequate technical systems' finally drive the systematic investment in operational protocols that water security demands?