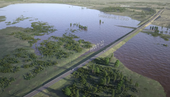

When Water Accounting Meets Reality: Why Agricultural Water Management Fails

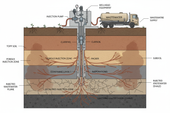

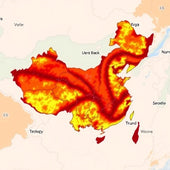

In Punjab, India's breadbasket, groundwater levels have dropped 40 meters in 30 years. Just 1.5 percent of India's total area produces 20 percent of its wheat and 12 percent of its rice, irrigated by four-fifths of the region's usable groundwater.

This catastrophic depletion didn't happen because anyone lacked knowledge about aquifer dynamics or sustainable extraction rates. It happened because water management agencies lacked the operational systems to monitor extraction, enforce limits, and optimize usage systematically. Punjab's crisis reveals the fundamental problem plaguing agricultural water management globally: sophisticated policy frameworks and ambitious targets fail completely without operational excellence in execution.

The Virtual Water Paradox

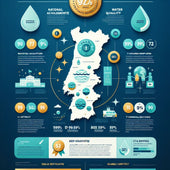

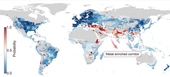

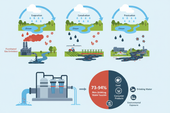

The concept of virtual water—the water embedded in the products we consume—provides powerful analytical frameworks for understanding global water flows. Germany consumes 219 billion cubic meters of virtual water annually, with 86 percent imported through irrigation-intensive agricultural products like fruit, nuts, rice, and vegetables. The scarcity-weighted water footprint methodology offers even more sophisticated analysis, accounting for both the water volume used and the scarcity level in the production region.

These frameworks enable important policy discussions about agricultural subsidies, trade patterns, and sustainability standards. The European Union's new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive requires firms to prevent pollution risks, particularly related to human rights abuses. Proposals for labeling requirements would display scarcity-weighted water footprints on food packaging. These policy interventions all depend on one critical assumption: that water management agencies can actually measure consumption accurately and systematically.

Here's the paradox: you cannot calculate virtual water footprints without systematic operational protocols for measuring water extraction and use. You cannot enforce scarcity-weighted standards without monitoring systems that generate reliable data. You cannot implement water-related agricultural subsidies without verification protocols that confirm compliance. The sophisticated analytical frameworks driving policy discussions assume operational capabilities that most water management agencies worldwide simply do not possess.

What Punjab Reveals About Operational Failure

Punjab's groundwater collapse illustrates what happens when policy exists without operational execution. India established groundwater management frameworks decades ago. Everyone understood the problem—extraction exceeded recharge, aquifer depletion threatened agricultural sustainability, and farmer debt from ever-deeper wells created social crisis. Yet groundwater levels dropped 40 meters anyway.

The failure wasn't about policy design. It was about operational execution. Water management agencies lacked systematic protocols for monitoring extraction across thousands of small-scale wells. They lacked enforcement mechanisms that could function without manual inspection of every farm. They lacked data systems that could track usage patterns and identify violations reliably. They lacked optimization frameworks that could help farmers reduce consumption while maintaining yields.

This operational gap meant that even well-designed policies couldn't deliver results. Extraction limits existed on paper but weren't monitored systematically. Pricing mechanisms were established but couldn't be enforced without reliable measurement. Technical assistance programs were created but couldn't scale without standardized protocols for implementation. The policy framework was sophisticated. The operational capacity was inadequate.

Europe's Emerging Crisis

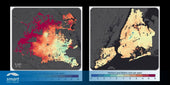

European countries face their own version of this operational challenge. Germany's irrigated area grew almost 50 percent between 2009 and 2022, from 372,700 to 554,000 hectares. Spain uses 82 percent of its water for agriculture, with significant pollution of both surface and groundwater. Forecasts show water stress in the European Union will increase by 2030, with available reserves increasingly unable to meet demand.

The proposed policy responses mirror the pattern: restructure the Common Agricultural Policy to reward water protection rather than hectare-based subsidies, implement labeling requirements for scarcity-weighted water footprints, establish due diligence standards for corporate supply chains. These policies could drive meaningful change—but only if water management agencies develop the operational systems to make them work.

Consider what it actually takes to implement scarcity-weighted water footprint labeling. Food producers need accurate data on water consumption at production sites. This requires monitoring systems with systematic measurement protocols, calibration procedures, and quality control frameworks. Water management agencies must verify reported consumption, which demands inspection protocols, data validation systems, and enforcement mechanisms. Supply chains spanning multiple regions need standardized reporting formats and data integration capabilities.

Every element of this implementation chain depends on operational excellence. Without systematic protocols for measurement, monitoring, verification, and enforcement, scarcity-weighted labeling becomes another policy framework that looks sophisticated on paper but fails in execution—exactly like Punjab's groundwater management regulations.

The Subsidy Reform Challenge

The proposal to shift EU agricultural subsidies from per-hectare payments to water protection rewards illustrates the operational excellence imperative even more clearly. The policy logic is sound: current subsidies incentivize production volume without regard to resource sustainability, while water-protection subsidies would reward conservation and efficiency. But implementing this shift requires operational capabilities most water agencies lack.

To distribute subsidies based on water protection performance, agencies must measure baseline water consumption reliably, verify conservation measures systematically, and quantify protection outcomes objectively. This demands standardized protocols for water use assessment, systematic monitoring of conservation practices, and data systems that can track performance across thousands of farms. Without these operational systems, water-protection subsidies become vulnerable to the same implementation failures that plague other well-intentioned agricultural policies: inconsistent measurement, unreliable verification, and enforcement that depends on manual inspection rather than systematic monitoring.

What Success Actually Requires

Some jurisdictions have demonstrated that agricultural water management can achieve both conservation and productivity—but always through operational excellence, not just policy frameworks. Australia's Murray-Darling Basin reform succeeded where many others failed because it invested heavily in operational systems: comprehensive water accounting frameworks with standardized measurement protocols, real-time monitoring systems with systematic data quality controls, and market mechanisms supported by reliable verification systems.

Israel's agricultural water efficiency didn't result from policy mandates alone. It came from operational systems that made efficient water use economically rational and technically achievable: precise irrigation technologies paired with systematic protocols for optimization, pricing mechanisms supported by accurate metering and enforcement, and extension services that could deliver technical assistance at scale through standardized training programs.

California's groundwater sustainability planning represents another instructive example. The state's Sustainable Groundwater Management Act establishes ambitious targets and comprehensive frameworks. But implementation success varies dramatically by region, with the difference explained almost entirely by operational capacity. Regions with systematic monitoring protocols, reliable data systems, and enforcement mechanisms show progress toward sustainability. Regions lacking these operational capabilities struggle to implement even basic management measures, regardless of policy sophistication.

The Measurement Foundation

Virtual water accounting, scarcity-weighted footprints, sustainability due diligence, and water-protection subsidies all share a common operational requirement: systematic, reliable measurement of water consumption. This measurement foundation cannot be built through policy mandates or analytical frameworks. It requires water management agencies to invest in the unglamorous operational work that makes sophisticated policies actually function.

Systematic measurement protocols that specify exactly how water use is quantified, when measurements occur, and how quality is verified. Calibration procedures that ensure monitoring equipment produces accurate data over time. Data quality frameworks that identify and correct errors systematically. Integration systems that aggregate information from multiple sources reliably. Verification mechanisms that confirm reported consumption without requiring manual inspection of every site.

These operational systems receive far less attention than policy frameworks and analytical methodologies. They're harder to explain in policy documents and less impressive in international forums. Yet they determine whether sophisticated policies like scarcity-weighted labeling or water-protection subsidies actually deliver results or become another layer of regulations that look good on paper but fail in execution.

What This Means for Water Management Agencies

The agricultural water crisis demands a fundamental reorientation of how water management agencies approach their role:

• Recognize that policy frameworks fail without operational execution. Punjab had groundwater regulations. Europe has sustainability directives. These policies didn't prevent crisis because agencies lacked operational systems to implement them. Before advocating for new policies, invest in the operational capabilities to execute existing ones.

• Build measurement systems before implementing market mechanisms. Virtual water footprints, scarcity-weighted labeling, and water-protection subsidies all require accurate consumption data. Agencies cannot implement these mechanisms without systematic measurement protocols, calibration procedures, and quality control frameworks. The measurement foundation comes first.

• Invest in verification systems that scale systematically. Manual inspection cannot verify water use across thousands of farms. Agencies need automated monitoring systems with systematic data validation, enforcement mechanisms that function without site visits, and compliance frameworks that identify violations reliably. Verification must be systematic, not episodic.

• Prioritize operational protocols over analytical sophistication. Scarcity-weighted water footprints provide valuable analytical insights—but only if consumption data is reliable. Agencies should invest in standardized measurement and reporting protocols before developing increasingly sophisticated analytical methodologies. Operational excellence enables analytical sophistication, not vice versa.

Beyond Policy Frameworks

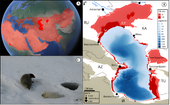

Agricultural water stress is accelerating globally. The world's irrigated area has doubled since 1961 and now produces 40 percent of global food production. Climate change is intensifying water scarcity in critical agricultural regions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts irrigation demand could double or triple by century's end. These pressures demand urgent action.

Policy frameworks addressing this crisis proliferate: virtual water accounting, scarcity-weighted footprints, sustainability due diligence, water-protection subsidies, corporate supply chain standards. These frameworks provide important analytical tools and create pressure for change. But Punjab's 40-meter groundwater decline demonstrates that sophisticated policies cannot compensate for operational inadequacy.

Water management agencies face a choice. They can continue developing increasingly sophisticated policy frameworks while neglecting the operational systems needed to implement them. Or they can recognize that operational excellence—systematic measurement protocols, reliable monitoring systems, scalable verification mechanisms, and standardized enforcement procedures—determines whether any policy framework actually delivers results.

The jurisdictions achieving agricultural water sustainability haven't done so through superior policy design. They've done it through operational excellence that makes policies function as intended. The question for water management agencies worldwide: when will you stop debating policy frameworks and start building the operational systems that make policies work?