Pakistan Uses Global Forum To Warn Of India’s Indus Waters Treaty Suspension Risks

The decision of Pakistan to bring up the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) by India at the Indo-Pacific Ministerial Forum Roundtable in Brussels signifies a diplomatic escalation and a strategic move to internationalize a dispute that has great implications for the stability of the whole region.

Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar, in his talk, pointed out what the Pakistani government considers to be the seriousness of the Indian government’s act: a direct confrontation not only with the long-standing water-sharing agreement between the two countries but also with the more general water-sharing agreements of the world. By putting forward the issue to a mixed multilateral audience, Pakistan made it clear that it wants to bring the topic up all over the world, portraying India’s suspension as a litmus test for the validity of international treaties in a world that is getting more and more divided.

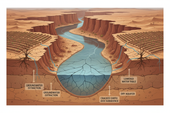

Dar underlined that Pakistan is still willing to use the IWT’s arbitration methods, especially those that involve a neutral expert review and the World Bank’s facilitation. Therefore, Islamabad considers its use of these methods as a proof of its accountable management of common resources and its unwillingness to make the river systems a matter of politics. On the other hand, Pakistan claims that India’s latest steps have conferred upon them the freedom to depart from the treaty’s – rules, which have even survived outright hostilities, such as the wars of 1965 and 1971. Pakistan believes that the IWT’s survival thus far is an indication of its resilience and the need to maintain its integrity, particularly when climate volatility is already a factor that may cause further hydrological instability in the Indus Basin.

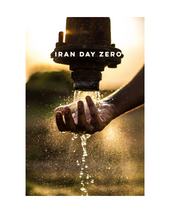

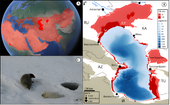

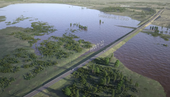

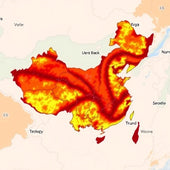

Islamabad cautioned that the consequences would not only be legal or symbolic. By indicating that the forecasted discharge of the Indus River and its tributaries is the lifeblood of millions of farmers and communities residing in the downstream area, Pakistan vividly portrays the scenario in terms of human and ecological values. For sure, any modification, whether feared or not, could provoke the water dispute just as the escalating temperatures, irregular rains, and melting glaciers are changing the water conditions in the area. Pakistan contends that the reduction in water supply would lead to a decline in food production, increase in hunger, and eventually, humanitarian crises that would impact more than 200 million people. Therefore, the Indian move is considered minimal in the light of the climate emergency and water distributions are regarded as an additional burden on the already overstrained environment in terms of both national and cross-border ecosystems.

The Brussels forum was a stage for Pakistan to announce these worries to a world that is getting more and more interested in the geopolitical aspects of resource competition. Islamabad’s story indicated that the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was not just a bilateral agreement but a landmark of transboundary water cooperation whose demise could have a domino effect on other areas with similar river management problems. Pakistan claimed that discarding such a long-standing and internationally-accredited treaty would not only undermine the trust in multilateral organizations but also the World Bank in particular, which has long been praised for its preventive diplomacy in conflict resolution through IWT and its mechanisms. By pointing out what it calls India’s continuous attempts to change or interpret treaty clauses over political or security incidents, Pakistan contended that the current suspension by New Delhi brings up the crucial issue of unilateralism and the future of cooperative resource governance, thus questioning the whole matter.

At the same time, Pakistan indicated its willingness to cooperate and progressive thinking by making its interventions in Brussels. Islamabad treated the current investments in dam constructions, modernization of irrigation systems, and water management reforms as a proof of its efforts for self-sufficiency, climate change adaption, and just resource sharing. Besides, Pakistan claimed that these projects would reverse the regional frailty narratives and instead the country would be seen as one that is overcoming hydropolitical challenges with its domestic resilience and unity with other countries. By the internationalization of the issue, Pakistan sought to convey that it does not want a confrontation but rather transparency, supervision, and reaffirmation of the established norms concerning the shared rivers.

Brussels was also the venue where Pakistan’s diplomatic message was louder than ever through its dialogue with wider global issues. The dispute over the Indus is a good example of the geographical resource tensions, which, if let unmediated, can easily turn into global political issues, with the Nile Basin and Central Asia being the other spots where such tensions are being experienced. Hence, by encouraging the participation of the multilateralism in the area, Pakistan was attempting to draw from an already existing global agreement that water security cannot be separated from peace, development, and climate action. Islamabad was asking the partners to see the IWT and similar arrangements just like the very fabric of global ecological management and sustainable development. Pakistan has put forth a point that keeping such pacts among others is a prerequisite for not only the prevention of environmental damage but also the establishment of trust among states sharing ecosystems.

It is still unclear if Pakistan’s diplomatic campaign in Brussels will be able to maintain and even increase the international pressure on countries through their help. However, the very intervention gives a glimpse of the big stakes involved. The dispute between Pakistan and India over the rivers governed by the Indus Waters Treaty has now come down to a point where it is not only a matter of environmental security but also geopolitical power play. By bringing up the matter at a high-level forum with stakeholders from the whole region and even further afield, Pakistan tried to ensure that the dialogue would not be limited to bilateral talks but rather become an integral part of the larger discussion on the governance of shared natural resources.

In the end, Pakistan’s communication in Brussels was a combination of warning and reaffirmation. It was a warning that the collapse of a treaty, with a history of being a model for conflict-tolerant cooperation, could lead to a dangerous global situation and an affirmation of the country’s commitment to the rules-based mechanisms that have availed the Indus Basin for more than 60 years. In doing so, Islamabad has emerged as a protector of global values as well as a state open to partnership in finding ways around the conjoined issues of water shortage, climate stress, and peace in the region.