There are documentaries that inform, and then there are documentaries that reshape how you see the world you work in every day. The Grab, directed by Gabriela Cowperthwaite (the filmmaker behind Blackfish), falls squarely into the second category. If you work in water operations, irrigation management, or any corner of the water infrastructure world, this film is essential viewing.

Released in 2024 by Magnolia Pictures and Participant, the documentary follows investigative journalist Nate Halverson and his team at the Center for Investigative Reporting over the course of six years. What they uncover is a sprawling, interconnected web of sovereign powers, private financial interests, and mercenary groups all racing to control the planet's most fundamental resources: food and water.

The Investigation That Reads Like a Thriller

The narrative begins with a seemingly straightforward corporate acquisition: the purchase of Smithfield Foods, the largest pork producer in the United States, by China's state-backed WH Group. That single transaction gave Chinese interests control over roughly one in four American pigs. But as Halverson digs deeper, the story expands into something far more systemic.

The film tracks Saudi-backed companies purchasing thousands of acres of arid Arizona farmland, where unrestricted groundwater pumping laws allow foreign investors to drain local aquifers to grow alfalfa destined for export. It follows Russian operations into regions where climate change is opening up once-frozen land for agriculture. It documents the activities of private military firms securing land deals across Africa, displacing communities from their ancestral territory.

When countries import food, they are often doing so as a proxy for water — and the world's most powerful nations know it.

— Core thesis of The GrabEach thread, examined alone, might seem like an isolated business story. Taken together, they reveal a coordinated pattern: nations and corporations positioning themselves for a future where water scarcity reshapes geopolitics as profoundly as oil did in the twentieth century.

Why This Matters for Water Operations

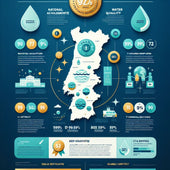

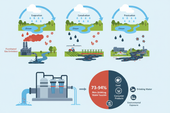

For those of us operating canal systems, managing irrigation districts, or running water treatment facilities, The Grab connects our daily work to the largest strategic contest of our era. The film illustrates a simple but devastating equation: global water use has surged 25% since 2000, with a third of that increase occurring in areas that are already drying out. Agriculture remains the dominant consumer, accounting for roughly 72% of all freshwater withdrawals worldwide.

The 2025 World Bank Global Water Monitoring Report puts the annual loss of freshwater at 324 billion cubic meters per year, enough to supply 280 million people. Meanwhile, FAO's latest AQUASTAT data shows renewable water availability per person has dropped 7% in just a decade. These are not projections for a distant future. This is the water balance sheet we are already living with.

In Alberta's irrigation districts, we see this tension firsthand. Our canals serve over 400 farms, and every operational decision about water allocation, conveyance efficiency, and loss management sits within this global context. The water we steward is part of the same finite system that nations are competing to control.

The Arizona Case Study: A Warning for Every Irrigation District

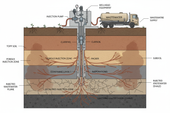

Perhaps the most striking segment for water operators is the Arizona story. In La Paz County, Saudi-backed agricultural companies legally pumped groundwater without restriction, growing alfalfa hay for export to feed livestock in the Middle East. Local farmers watched their wells go dry. The aquifer that had sustained generations of families was drained to support agriculture on another continent.

This is the kind of scenario that should keep every irrigation district manager awake at night. It demonstrates what happens when water governance fails to account for the strategic value of the resource. It also underscores why operational metrics, water use efficiency tracking, and transparent allocation frameworks are not just administrative tasks. They are the front line of water security.

Food, Water, and Geopolitical Power

The film draws direct connections between water resources and political stability. It references the Great Chinese Famine and the Arab Spring as historical examples of what happens when food systems collapse. It argues that Russia's invasion of Ukraine was driven in part by control over a nation that supplies a significant share of global wheat exports, noting that one of the first military objectives was to secure the canal infrastructure connecting the Dnieper River to Crimea.

For water operators, this reframes our infrastructure in strategic terms. The canals, reservoirs, pipelines, and SCADA systems we maintain are not merely utility assets. They are components of a nation's food security architecture. When we invest in asset management, telemetry upgrades, and operational efficiency, we are fortifying a link in a chain that extends from local farms to global stability.