Not a drop? Kabul may be the first city to run out of water

Water on credit – this is not a scenario from a science-fiction movie, but a daily reality for millions of residents of the Afghan capital. According to experts from UNICEF, the aquifers here are in danger of being completely depleted by 2030. Kabul could become a model example of the socioeconomic consequences of an extreme water deficit within a few years.

The dramatic situation in Kabul is described in a report by the NGO Mercy Corps, Kabul’s Water Crisis. An Inflection Point for Action. According to its authors, immediate intervention is needed to prevent a humanitarian disaster unprecedented in the world.

Kabul loses last water resources

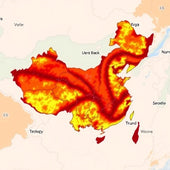

The population of the Afghan capital has increased sevenfold over the past quarter century. These demographic pressures and a lack of regulation have led to a crisis that the international media are already calling existential. Geographical conditions unfortunately do not help.

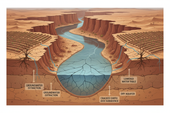

Kabul is located in a narrow valley of the Hindu Kush mountain range, far from natural bodies of water. The main artery of the valley is the Kabul River with two tributaries, the Logar and Paghman. All three of these watercourses depend on the rate of melting of the snowpack in the mountains – in spring flows can be as much as 15 times higher than in winter.

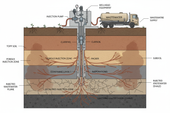

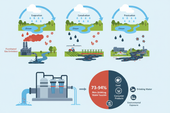

It is the seepage of water from the riverbed that is the main source of recharge for the aquifers under the Afghan capital. Their original volume was 5 billioncubic meters and was sufficient to cover the needs of the city’s population of seven million. However, overexploitation of water resources combined with climatic shocks have caused the level of aquifers under Kabul to drop by 25-30 meters over the past decade.

According to experts at Mercy Corps, groundwater abstraction in the Afghan capital exceeds aquifer recharge by 44 millionm3 per year. The water rationing is the result of the lack of a centralized system – most of the local population obtains water from more than 120,000 unmonitored wells.

Sewage, salt and arsenic

Kabul’s water shortage is only one part of the problem. The other is heavy contamination, which affects up to 80 percent of groundwater. A 2009 U.S. geological study found concentrations of boron, lead, selenium, arsenic and uranium exceeding World Health Organization standards. The reasons for this condition are mining activities, uncontrolled discharges of wastewater from industrial plants and the lack of comprehensive sewage systems. Most of Kabul’s residents still use latrines.

Seventy percent of local people complain that water in wells is stained, salty, and has an unpleasant taste or smell. Groundwater salinity is observed throughout Afghanistan. It is due to geological conditions and the low frequency of rainfall. In Kabul, however, its level is even higher due to the intense shrinkage of aquifers.

Water more expensive than food

Most of Kabul’s residents already suffer from water shortages. The average supply is 20 liters per person per day, four times less than the recommended minimum. Faced with poor quality well water, more and more families are forced to buy it from private suppliers, who do not hesitate to cash in on the dire humanitarian situation.

Over the past five years, water prices in Kabul have doubled and even tripled in some neighborhoods. According to Mercy Corps experts, many families spend 15-30 percent of their household budgets on the resource, which, after all, is impossible to live without. In Khair Khana district, weekly expenses for this reason are sometimes higher than the cost of buying food. 68 percent of households already have water debts, and informal loans – the only ones available to poor citizens – carry interest rates of 15-20 percent.

The agricultural sector is also suffering from water scarcity and salinity. Reduced production is pushing up the price of staple foods, putting additional pressure on already indebted families. Wheat has already become 40 percent more expensive since 2021, and crops in the more than 400 greenhouses operating around Kabul are also at risk.

World Bank data shows that Afghanistan’s GDP declined by 20.7 percent between 2021 and 2022, with more than $1.2 billion in economic losses associated with the water crisis.

International financial support on hold

The dramatic water situation in Afghanistan has been mobilizing the global humanitarian sector for years. However, an inept and bureaucratic government administration does not make it easy to implement WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) projects. NGOs trying to help spend months in a melee with ministries.

Strictly political considerations have also weighed on the water situation in Kabul. International organizations suspended $3 billion in funding, originally earmarked for water and sanitation investment, due to the Taliban’s return to power. Another economic blow came from Donald Trump’s decision to drastically reduce the USAID aid fund.

What can save Kabul?

Afghanistan received more than $4 billion in international support for water management between 2002 and 2021. Unfortunately, many investments turned out to be misguided, some were not completed. The city still lacks basic water and sewage infrastructure. First and foremost, a water pipeline is needed to deliver clean water directly to homes, replacing the current system of contaminated wells.

High hopes are being pinned on the construction of the Shahtoot Dam, subsidized by the Indian government, which is expected to provide potable water to 2 million Kabul residents. Its construction has unfortunately not yet begun, and the entire process is being blocked by Pakistani authorities. The crisis in the Afghan capital could also be alleviated by a 200-kilometer water pipeline, which would bring water to the city from the distant Panjshir River. The technical design was completed in 2024, but an environmental impact decision and the most important, financing, are still missing.

Mercy Corps experts stress that the situation in Kabul requires international attention. This is because the humanitarian crisis of depleting water resources will lead to mass migrations and increase political tensions throughout the region. India and Pakistan are already scrambling for water, and throughout Afghanistan water shortages are leading to malnutrition and the spread of waterborne diseases.

If nothing changes, within the next decade Kabul could become the first capital in the world to literally run out of water.

MAIN PHOTO: Faruk Tokluoğlu/Pexels