The world’s largest dam will be built on the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet. Who will benefit and who will suffer?

Last Saturday, a colossal Chinese hydropower project began on the Tibetan Plateau, aiming to transform the renewable energy market. The world’s largest dam will be constructed on the Yarlung Tsangpo River and is expected to generate 300 billion kWh annually. However, the idea has sparked international controversy – India and Bangladesh are loudly protesting.

Bigger than the Three Gorges Dam

The new Chinese structure is estimated to cost around $167 billion and will become the largest dam in the world – its energy capacity will be three times greater than that of the Three Gorges Dam, completed in 2006. The construction permit was issued in December 2024, and work on the project began last Saturday. According to the Xinhua News Agency, Chinese Premier Li Qiang participated in the official groundbreaking ceremony in the city of Nyingchi.

The project is scheduled to be completed by 2033, with a target hydroelectric capacity of 60,000 MW. The electricity generated will mainly be transported to other regions but will also partly meet Tibet’s energy needs. The official goal of the venture is to bring China’s economy closer to carbon neutrality, and a new company, China Yajiang Group – 100% government-owned – has been established to manage it.

The hydrological context of construction

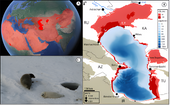

The Yarlung Tsangpo is the longest river in Tibet and the fifth longest in China. Originating near Mount Kailash in the northern Himalayas, it flows across the Tibetan Plateau, carving out the deepest and longest canyon on Earth – the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon (504.6 km deep).

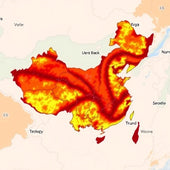

After leaving Tibet, the Yarlung Tsangpo becomes the Brahmaputra River and flows through the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam before entering Bangladesh. It’s no surprise that India and Bangladesh are the strongest opponents of the dam’s construction, fearing it could endanger their water security and thus food production. Authorities in Arunachal Pradesh have even expressed concerns that China could use the new infrastructure for military purposes, intentionally flooding or drying out specific regions.

In total, 718 billion m³ of water flow annually from the Chinese-controlled Tibetan Plateau and regions of Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia to neighboring countries – 48% of this supports India’s water resources.

The world’s largest dam stirs ecological and political controversy

Global media suggest the new Chinese dam could be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it represents a major step forward for China’s energy transition; on the other, it may disrupt water relations and ecosystems across the Tibetan Plateau. Local infrastructure and the job market will benefit, but water stress could be felt widely throughout the region.

Chinese authorities insist that the project has undergone a rigorous environmental assessment and that the dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo will not negatively affect the natural environment, the geological stability of the region, or the hydrological situation in downstream countries.

However, this optimistic government narrative is disputed by Chinese environmentalists. Experts cited by the Yale School of the Environment argue that the canyon where the dam will be built is a biodiversity hotspot of global significance, home to some of Asia’s oldest and tallest trees. The area also hosts an exceptionally rich mosaic of large predatory mammals, including rare wild cats. Environmental changes triggered by the dam’s construction could prove both far-reaching and irreversible.

Ameya Pratap Singh of the University of Oxford commented on the project from a political perspective, stating that the new dam will allow China to effectively strangle India’s economy. Mehebub Sahana of the University of Manchester adds that the militarization of water resources is a dangerous strategy that could backfire. In his view, the weakening of water diplomacy in South Asia threatens global climate security.

main photo: Guyin Lee/Wikimedia