River of the Anthropocene

River of the Anthropocene

Could the Mekong River define SE Asia’s future?

By Jonathan Zhao

With reporting and photographs by J. Carl Ganter

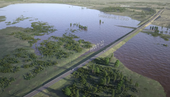

It is midday in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. The Mekong River, having mixed with the silty waters of the Tonle Sap, takes on the appearance of a muddy highway with a storm of activity. Fishermen are trawling and repairing their nets. Families are living in floating homes near the riverbank. Excavators pull sand out of the riverbed into waiting barges.

For the people of Phnom Penh and beyond, the Mekong has always given freely but now is reaching the limit of what it can provide.

In 802, King Jayavaraman II established the Khmer Empire, which would dominate Southeast Asia for over 600 years and whose culture is survived by present-day Cambodia. Jayavaraman II strategically built the capital city, Angkor, near the Tonle Sap Lake, where it could take advantage of large floodwater reserves to maintain bountiful rice harvests even during dry seasons.

Although the Khmer Empire is long gone, the use of the Mekong river system has only increased with population growth and the advancement of technology. In many areas around the world, but especially Cambodia, negligence and overextraction of resources are harming the waterways that people depend on.

The Anthropocenes Network, a collaboration of scientists, policymakers and artists, summed it up perfectly in the title of their keystone project: Rivers of the Anthropocene. As the greatest benefactors and highest authority over the world’s waters, humanity must acknowledge its responsibility to protect the natural environment, even if only for its own survival.

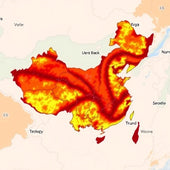

The Mekong River begins in China, where it is called the Lancang River. Much of the water at the source comes from snowmelt on the Tibetan Plateau, which accounts for 16% of the river’s flow. The river then passes through Laos, and its hydrology begins to change as tributaries merge. By the time the Mekong reaches Phnom Penh, it has reached over 95% of its total flow. Finally, it empties into the South China Sea via southern Vietnam. The majority of the 65 million people living in the Lower Mekong River Basin depend on the river for its natural resources.

“[The Mekong] has every single anthropogenic impact that we know, and each of them plays a critical role in impacting the river,” said Edward Park, an assistant professor of physical geography at Nanyang Technological University who has studied tropical rivers extensively.

This river system is the basis of millions of livelihoods, enabling transportation, agriculture, fishing and electricity generation. It is precisely because of this reliance that the current relationship of abuse and exploitation is untenable, and the recent withdrawal of USAID puts the goal of good stewardship even further out of reach. Changing weather patterns, loss of biodiversity and pollution threaten to upset the region’s way of life. Yet not enough attention is given to the river’s care by the local government or population.

Located in southern Cambodia, Phnom Penh is a vibrant city home to 2.5 million people. Thanks to foreign investment and a growing population over the last few decades, the city has undergone rapid modernization of its infrastructure, and several satellite cities have been constructed.

Phnom Penh’s history is anything but peaceful, however. During the brutal rule of the Khmer Rouge from 1975-1979, the entire city was evacuated and hundreds of thousands were killed in what is now recognized as state-sponsored genocide. As a result, over 65% of Cambodia’s population is under the age of 30, the descendants of those who survived.

The Tonle Sap Lake, Southeast Asia’s largest freshwater lake, lies 75 miles northwest of Phnom Penh and benefits from the yearly monsoon season, which reverses the flow of the Tonle Sap River from August through November and restocks the lake with fish fry. In 2023, the combined river and lake system provided over 500,000 tons of fish, about 70% of the Cambodian fishing industry.

In recent years, however, inconsistent rain and illegal fishing have decreased the productivity of the Tonle Sap. Juvenile fish populations have been devastated by shrinking habitats and overfishing, reducing reproduction rates and therefore future fish stocks. Families struggle to make ends meet despite working harder and harder. By 2030, the Tonle Sap Lake region is expected to lose 40-57 percent of its production.

In 2022, almost 30% of Cambodia’s electricity, about 1,331 megawatts, came from hydropower. A year later, the government approved proposals for two hydroelectric plants worth $447 million on the grounds that they would increase the availability of electricity, create jobs and spur economic growth. Cambodian Minister of Mines and Energy Keo Rattanak boasted that his country led Southeast Asia in clean energy thanks to massive investments in hydropower.

Unfortunately, the expansion of hydropower has its downsides. Hydropower dams necessarily block the flow of water, negatively affecting downstream ecosystems and, in turn, communities that rely on fishing. Cambodia has postponed the construction of two dams upstream of the Tonle Sap River in order to review potential ecological impacts, but locals are concerned that recent feasibility studies conducted by the government signal the revitalization of the project.

As with many river systems located near or within large urban areas, the Tonle Sap suffers from severe plastic pollution. Industrial and household waste drifting down the Mekong River is eventually carried into the Tonle Sap Lake by the yearly monsoons, where it clogs up trawling nets and stunts the growth of fish by introducing toxins into the water.

The issue of pollution has caught the attention of the Cambodian government, which has been encouraging the population to reduce their use of single-use plastics. This approach ignores the larger problem of waste management, however, meaning that wantonly discarded plastics continue to pile up in the river without significant cleanup efforts in response.

In order to fuel the construction boom in Phnom Penh, sand mining operations on the Tonle Sap/Mekong River around the city have intensified, especially since mining regulations went unenforced during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, Cambodia extracted 59 million tons of sand from its portion of the Lower Mekong region.

“If you zoom into any random place in the Mekong River in Vietnam, you can see sand extraction going on with big barges and small extraction pumps,” said Park.

At the same time that sand is taken from the river to build infrastructure in the city, housing along the river is being removed. Large-scale excavation of the riverbed wreaks havoc by eroding the riverbanks, displacing residents who live near the water. The resulting deepening of the river is also shrinking the Tonle Sap Lake upstream, harming the fishermen and farmers who have historically thrived on high water levels.

In the 2024/2025 fiscal year, Cambodia grew 8.47 million tons of rice, making it the 10th-largest producer of rice despite having significantly less arable land than its competitors. Within the country, areas adjacent to the Tonle Sap Lake and River are the most productive due to the irrigation provided by the yearly monsoon. In fact, some farmers grow “floating rice,” a practice in which the rice is sown onto dry land so that it gets flooded during the Tonle Sap Lake’s annual expansion.

Changing hydrological conditions, however, have rendered agriculture impractical in some areas, driving farmers into the city to look for work. Not only has the yearly reversal of the Tonle Sap River become unreliable, but rising sea levels in conjunction with sediment extraction increase the risk of saltwater intrusion, which is already ruining rice crops in coastal areas.

Even though some aspects of the Mekong’s use, such as sand mining, can be regulated by the Cambodian government, others are harder to control. Park explained that upstream countries like China are able to build dams and divert water with impunity, leaving Cambodia and Vietnam with few means of protest. Climate change is an even thornier issue, the effects of which may be impossible to reverse without global cooperation.

“Not many things can be done by a single country,” said Park. “We really need a concerted effort across different countries.”

Despite the damage done to the Mekong and Tonle Sap Rivers, the solution is not to eliminate humanity’s impact on the rivers, but for people and the natural environment to coexist for the benefit of future generations. It is a lofty goal, but it can be achieved through a combination of good governance, international awareness, and a concerted effort by the local people to care for the resource they rely on every day.

Photo Gallery

Rocky islands and other obstructions prevent large ships from operating on the Mekong upstream of Phnom Penh. Smaller boats and ferries are used on the Tonle Sap and Mekong for some transport of goods, primarily fish products.

Lead image: © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

The post River of the Anthropocene appeared first on Circle of Blue.