Mexico's Water Reforms: A Turning Point for Irrigation District Management

Mexico's Water Reforms: A Turning Point for Irrigation District Management

November 8, 2025

Mexico stands at a pivotal moment in water governance. President Claudia Sheinbaum's administration has proposed sweeping reforms that fundamentally redefine how the nation manages its most vital resource—with profound implications for irrigation districts across North America.

vital resource—with profound implications for irrigation districts across North America.

The Reform Landscape

On October 1, 2025, President Sheinbaum submitted legislation to enact a new General Water Law and reform the existing National Water Law. These aren't minor policy adjustments; they represent a paradigm shift in water management philosophy. The reforms aim to transform water from a tradable commodity into a national strategic resource, with strict prohibitions on private concession transfers and significantly enhanced penalties for violations.

The legislative package builds on a constitutional amendment from 2012 that recognized access to water as a fundamental human right—a mandate that remained unfulfilled for over a decade until now. After extensive public forums in early 2025 titled "Transforming the Water Regime in Mexico," the government consolidated input from irrigation districts, Indigenous communities, municipalities, and civil society into comprehensive reform proposals.

Historic Investment in Irrigation Infrastructure

Perhaps most striking for irrigation professionals is the announced investment: more than 60 billion Mexican pesos dedicated specifically to irrigation district modernization under the "México se Tecnifica" initiative. This historic funding commitment signals recognition that irrigation efficiency isn't just about water conservation—it's fundamental to food security, agricultural productivity, and rural community sustainability.

The National Water Plan 2024-2030 projects 122.6 billion pesos in total water infrastructure investments over six years, with irrigation modernization receiving priority attention. The government is focusing on:

Technology adoption: Modern irrigation systems to reduce water loss through evaporation and surface filtration

Infrastructure upgrades: Distribution system improvements in irrigation districts

Crop adaptation: Supporting cultivation of lower water-demand crops, particularly in arid regions

Wastewater reuse: Expanding treated wastewater use for irrigation (excluding raw-consumption vegetables)

Structural Governance Changes

The reforms introduce several institutional changes that irrigation districts worldwide should note:

National Water Registry for Wellbeing (RENAB)

This new digital registry aims to bring transparency and efficiency to water rights management. The government is streamlining procedures from 27 to 19 processes and from 19 to 9 requirements, with maximum response times capped at 60 days. For irrigation districts managing thousands of water users, digitization represents both an opportunity and a necessity.

Socio-Hydric Impact Evaluations

New water concessions will require independent third-party impact assessments. This creates accountability but also adds complexity and cost to the approval process. The requirement reflects growing recognition that water allocation decisions carry cascading social, economic, and environmental consequences.

Water Rights Transfer Center

Perhaps most controversial is the provision that unused treated wastewater automatically reverts to a new Water Rights Transfer Center within CONAGUA (Mexico's National Water Commission). This effectively ends private control over wastewater reuse—a significant departure from market-based water management approaches.

The Irrigation District Context

Mexico operates extensive irrigation infrastructure serving agricultural production that accounts for significant export value. Agriculture currently consumes 77% of Mexico's water resources, particularly in the arid northern regions most affected by climate change. Irrigation districts are caught between competing pressures: increasing efficiency, maintaining agricultural output, and adapting to more restrictive regulatory frameworks.

The reforms include provisions to improve small-scale farmer access to water rights and irrigation energy subsidies. This social equity dimension recognizes that water allocation isn't purely a technical or economic question—it reflects fundamental decisions about who benefits from scarce resources.

Legislative Uncertainty and Implementation Challenges

Despite the government's strong parliamentary majority and expectations that reforms will pass, significant uncertainties remain:

Budget constraints: CONAGUA's 2025 federal budget faces a projected 40% reduction, raising questions about enforcement capacity and program delivery capability.

Resistance to change: Industrial and agricultural concession holders who benefit from existing arrangements are likely to challenge new restrictions, particularly the ban on concession transfers.

Institutional capacity: Implementing new systems like RENAB, training specialized water law judges, and conducting socio-hydric impact evaluations requires substantial technical expertise and resources.

Climate vulnerability: Mexico faces increasing drought severity and water scarcity. The reforms arrive as the country grapples with aquifer overexploitation—some regions extract water at 2.5 times the natural recharge rate.

Lessons for Canadian Irrigation Districts

While Canada's water governance operates under fundamentally different legal and institutional frameworks, Mexico's experience offers instructive parallels:

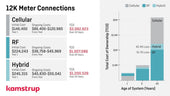

1. Digital Transformation is Non-Negotiable

Mexico's push to digitize water rights registries and streamline procedures reflects a global trend. Irrigation districts that still rely on paper-based systems or manual water order processing face mounting pressure to modernize. Tools like Watervize and similar platforms aren't luxuries—they're becoming operational necessities.

2. Water as a Right vs. Water as a Commodity

The philosophical tension between treating water as a human right versus a market commodity exists in Canada too. Alberta's Water for Life strategy and irrigation district legislation balance these competing frameworks, but climate change and growing municipal demands will intensify debates about allocation priorities.

3. Infrastructure Investment Needs Political Will

Mexico's 60+ billion peso irrigation commitment demonstrates that modernization requires sustained political and financial support. Canadian irrigation districts face similar infrastructure renewal challenges, with aging canal systems, pump stations, and conveyance structures requiring systematic upgrading.

4. Regulatory Independence Has Value

Under Section 191 of Alberta's Irrigation Districts Act, irrigation districts maintain considerable regulatory independence—they can establish agreements, bylaws, and rates without Public Utilities Act oversight. This autonomy provides flexibility that centralized systems like Mexico's may struggle to achieve.

5. Stakeholder Engagement is Essential

Mexico's multi-stakeholder forums brought together diverse voices before finalizing legislation. Successful water governance requires incorporating perspectives from producers, municipalities, environmental groups, and Indigenous communities—not dictating policy from centralized agencies.

The Road Ahead

Mexico's water reforms represent an ambitious attempt to address decades of policy paralysis and respond to escalating water security challenges. Whether they succeed depends on effective governance, transparent enforcement, adequate funding, and collaborative implementation.

For irrigation professionals globally, Mexico's experience highlights fundamental questions:

How do we balance agricultural water needs with growing urban demand and environmental protection?

What role should market mechanisms play in water allocation?

How can we modernize infrastructure and management practices with constrained budgets?

What governance structures best serve diverse stakeholder interests?

These aren't uniquely Mexican challenges. As climate change intensifies water scarcity, irrigation districts everywhere must adapt. Mexico's bold reforms—with both their promise and their uncertainties—offer a real-time case study in how one nation is attempting to chart a new course.

The legislation's passage appears likely given the ruling party's parliamentary majority. Implementation will take years. But the direction is clear: water governance is shifting from market-oriented commodity management toward recognition of water as a strategic public resource essential for national security, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

For Canadian irrigation districts comfortable with our existing frameworks, Mexico's experience serves as both a caution and an inspiration—a reminder that water governance must continually evolve to meet changing conditions, and that the status quo is not a permanent option when facing climate reality.

For irrigation operations managers and water professionals interested in discussing these developments and their implications for North American irrigation district management, these reforms merit close attention as they unfold through 2025 and beyond.