When Civilizations Run Dry: The Timeless Pattern of Irrigation Mismanagement

When Civilizations Run Dry: The Timeless Pattern of Irrigation Mismanagement

The ancient Mesopotamians built the world's first engineering marvels—sophisticated canal networks that transformed seasonal deserts into agricultural powerhouses. The Classic Maya developed ingenious reservoir systems and hydraulic technologies that sustained millions in a challenging environment. These weren't primitive societies stumbling in the dark. They were advanced civilizations with remarkable technical capabilities.

Yet both collapsed. And the cause wasn't what most people assume.

The Real Culprit: Not Drinking Water, But Agricultural Depletion

When we think about water and civilization collapse, we imagine cities running out of drinking water—people dying of thirst, communities fleeing in search of water sources. But history tells a different story. Ancient Mesopotamia and the Maya didn't collapse because their populations couldn't find water to drink. They collapsed because their irrigation systems depleted the water resources needed for agriculture, and they lacked the operational frameworks to manage those systems sustainably.

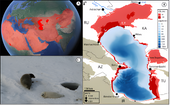

In Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, irrigation brought water to fields faster than it could drain out. As salt-rich groundwater rose and surface water evaporated, mineral salts built up in the soils. Farmers switched to more salt-tolerant grains like barley, but the harder they farmed, the less they harvested. After about 2,000 years, the once-fertile land of southern Mesopotamia was barren. The Code of Hammurabi from 1790 BCE devoted hundreds of laws to irrigation systems and water distribution—evidence that even early rulers recognized the challenge. But laws alone couldn't solve a problem that required systematic operational protocols.

The irrigation systems themselves were engineering triumphs. Archaeologists have discovered 3,300-year-old plow furrows near Ur in southern Iraq with water jars still lying by small feeder canals. These systems supported denser populations than live in those areas today. The technology worked. What failed was the management system—the unglamorous work of monitoring soil salinity, coordinating drainage schedules, managing extraction rates, and maintaining communication protocols between upstream and downstream users.

The Maya civilization tells a parallel story. They created sophisticated water management systems including chultuns (underground cisterns), aguadas (artificial reservoirs), and complex canal networks. At Tikal, reservoirs held enough water to meet drinking needs for 10,000 people for 18 months. The engineering was impressive. The problem emerged when drought hit during the Terminal Classic period (800-950 CE), with rainfall reductions between 41 and 54 percent, and up to 70 percent during peak drought conditions.

But here's what matters: the Maya had previously survived droughts. What changed wasn't the climate alone—it was the scale of their operations without corresponding operational capacity. As populations grew and agricultural demands increased, they overexploited water resources and deforested vast areas. When drought struck, they lacked the systematic protocols to adapt their water usage, coordinate regional responses, or manage competing demands. Cities in the central Maya lowlands experienced population declines approaching 90 percent.

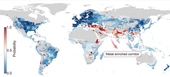

The Pattern Repeats: Modern Groundwater Depletion

Four millennia after Mesopotamian farmers watched their yields decline, and over a thousand years since Maya cities were abandoned, we're witnessing the same pattern unfold globally. The technology has changed—electric pumps replaced shadoofs, satellite monitoring tracks aquifer levels—but the fundamental failure remains identical: sophisticated infrastructure deployed without systematic operational protocols.

The United States: High Plains Aquifer

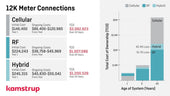

The Ogallala Aquifer beneath the US High Plains represents America's agricultural foundation, providing 30 percent of the nation's irrigation water. Recent research reveals a troubling trajectory: 35 percent of the southern High Plains will be unable to support irrigation within 30 years if current depletion continues. The aquifer has lost 330 cubic kilometers of fossil groundwater—water that accumulated over 13,000 years.

The challenge isn't a lack of technology. Farmers have access to center-pivot irrigation systems, soil moisture sensors, and sophisticated pumping equipment. The challenge is operational: depletion is highly localized, with about one-third occurring in just 4 percent of the High Plains land area. When aquifers thin, well yields decline even when substantial water remains, making extraction increasingly difficult during droughts. Farmers atop groundwater 330 feet thick irrigate 89 percent of their corn acres, while those above 30-foot aquifers irrigate just 70 percent.

The agricultural production system depends entirely on systematic coordination that largely doesn't exist: monitoring extraction rates across thousands of users, enforcing sustainable pumping limits, coordinating reduction schedules, and managing competing demands. The expensive wells and irrigation equipment are worthless without protocols to prevent exactly what destroyed Mesopotamia—progressive depletion that makes agriculture impossible even when water technically remains.

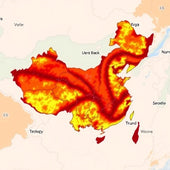

India: The World's Largest Groundwater Consumer

India provides groundwater for 60 percent of its irrigation, supporting 10 percent of global agricultural production. The northwest and south face critically low groundwater availability by 2025. A University of Michigan study projects groundwater depletion rates will triple by 2080, primarily driven by irrigation. Current research suggests cropping intensity may decrease 20 percent nationwide and 68 percent in depleted regions.

India's post-Green Revolution era transformed agriculture through tube well construction starting in the 1960s, allowing farmers to expand into dry seasons and increase cropping intensity. The technology delivered remarkable food production gains. What wasn't developed systematically were the operational protocols to prevent overextraction: monitoring systems tracking thousands of tube wells, enforcement mechanisms for extraction limits, communication frameworks between users, and coordination protocols for regional management.

Punjab attempted policy interventions by prohibiting early paddy sowing before specified dates, with penalties for violations. These represent the exact approach that failed ancient Mesopotamia—passing laws without building operational capacity to monitor compliance, coordinate water users, and systematically manage the resource. The sophisticated agricultural technology operates within a management vacuum, depleting aquifers through uncoordinated individual extraction.

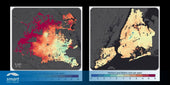

California Central Valley: Intensive Depletion

California's Central Valley, ranked second among US aquifers for total groundwater withdrawals, experiences the highest groundwater depletion intensity due to increased use over recent decades. The valley accounts for approximately 50 percent of US groundwater depletion since 1900. With 53 percent cropland and 90 percent of cropland and pastureland irrigated, the region's agricultural productivity depends entirely on groundwater during drought periods.

The consequences mirror ancient patterns: loss of long-term water supply, increased pumping costs as water tables decline, productivity loss in wells requiring reconstruction, land subsidence, and the shifting of cultivation patterns. The Central Valley has world-class irrigation technology, satellite monitoring, and sophisticated well construction. What it lacks are the systematic operational protocols that would prevent depletion: coordinated extraction schedules, enforced sustainable pumping limits, shared monitoring systems, and regional management frameworks.

Mississippi: Humid Region Depletion

Even in Mississippi's Big Sunflower River Watershed, a humid region receiving substantial rainfall, groundwater levels drop 0.2 to 0.5 meters during crop irrigation seasons from May to August. Corn, soybean, and rice consume approximately 96 percent of total groundwater irrigation. Annual recharge rates are only 34-50 millimeters, while the watershed loses 381-749 millimeters annually through surface runoff depending on conditions.

Recent modeling suggests irrigation scheduling based on plant water demand could save 47 percent of currently used groundwater and reduce groundwater decline by 0.01-2.05 meters across the watershed. This represents the operational solution that ancient civilizations never systematized: scheduled application protocols, demand-based allocation, coordinated regional management. The challenge isn't developing the science—researchers can model optimal schedules. The challenge is implementing systematic protocols across thousands of farmers with competing interests and limited coordination mechanisms.

The Core Failure: Infrastructure Without Operations

Across all these examples—ancient and modern—the pattern is identical. Societies invest enormous resources in infrastructure and technology. Mesopotamians dug canals. The Maya built reservoirs. Modern farmers install center-pivot systems and deep wells. The US has constructed monitoring networks and research programs. India built millions of tube wells. California has developed satellite monitoring systems.

None of it matters without operational protocols.

The expensive infrastructure becomes worthless—or actively destructive—without the unglamorous work of systematic procedures: Who monitors extraction rates? How are conflicts between upstream and downstream users resolved? What protocols govern reduction during drought? How are individual actions coordinated into sustainable regional management? What communication systems ensure all users understand current conditions? Who enforces compliance with extraction limits?

This mirrors the core insight from Atul Gawande's "The Checklist Manifesto"—organizations approve millions for SCADA systems and treatment technology while underinvesting in operational protocols that determine whether expensive assets actually deliver consistent performance. Water utilities will spend $50 million on advanced treatment facilities but won't invest $500,000 in systematic communication protocols and operational procedures. The same pattern drives aquifer depletion globally.

The Contemporary Policy Framework

Modern water management initiatives consistently repeat this error. Policy frameworks emerge—groundwater sustainability plans, extraction limits, monitoring requirements—but without building operational capacity to implement them. Punjab prohibits early paddy sowing with penalties for violations, but who monitors thousands of farms? Who enforces penalties? What communication system informs farmers of current extraction status? The policy exists; the operational system doesn't.

The International Water Association and ISO 24516 provide frameworks for water loss management, acknowledging that utilities need systematic protocols. WHO Water Safety Plans recognize that drinking water safety depends on operational procedures, not just treatment technology. Yet irrigation management—which consumes 70 percent of global freshwater withdrawals—lacks equivalent operational frameworks despite catastrophic consequences when management fails.

Lessons From History, Ignored

The historical record couldn't be clearer. Advanced civilizations with impressive engineering capabilities collapsed when irrigation systems depleted their agricultural water sources. They had the technology. They built remarkable infrastructure. What they lacked were the systematic operational protocols to manage extraction sustainably across competing users.

We're repeating their failure at a global scale. The US High Plains will lose agricultural capacity supporting the nation's food security. India faces a 68 percent decrease in cropping intensity in depleted regions, threatening 10 percent of global agricultural production. California's Central Valley continues intensive depletion despite sophisticated technology. Even humid Mississippi depletes groundwater during irrigation seasons.

The solution isn't more technology. It's not better monitoring equipment or deeper wells or more efficient irrigation systems. Those help, but they're worthless without systematic operational protocols. The solution is the unglamorous work that organizations consistently underinvest in: building communication systems between water users, developing enforcement mechanisms for extraction limits, creating coordination protocols for regional management, and establishing monitoring frameworks that translate data into operational decisions.

Until we recognize that expensive infrastructure is worthless without systematic operational protocols—exactly as Mesopotamia and the Maya discovered—we'll continue depleting aquifers that took millennia to form. The civilizations that come after us will study our ruins and ask the same question future generations asked about the Maya: how could such an advanced society make such an obvious mistake?

The answer is the same now as then: we invested in technology, not operations. We built infrastructure, not management systems. We developed sophisticated tools without systematic protocols to use them sustainably.

History repeats because we refuse to learn its fundamental lesson about operational excellence.