The First Water Utility Manager: Frontinus vs. Modern Utilities

The First Water Utility Manager:

Frontinus vs. Modern Utilities

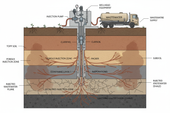

In 97 AD, the Emperor Nerva handed Sextus Julius Frontinus one of the most consequential administrative appointments in Roman history: curator aquarum—commissioner of water. Frontinus inherited oversight of nine aqueducts serving a city of over one million people, a network spanning roughly 800 kilometres of conduit delivering an estimated 500 to 1,000 cubic metres of water daily.

What he found was a system in crisis—not because Rome lacked infrastructure, but because it lacked operational discipline. Aqueducts had been neglected and were not working at full capacity. Channels were silted. Unauthorized diversions riddled the network. A practice Frontinus termed fraus aquariorum—plumbing fraud—saw farmers, tradesmen, and even operators of “disorderly houses” tapping directly into conduits. Underground leaks, difficult to locate, drained capacity that never reached Roman citizens. Corrupt officials took bribes to look the other way. Pipes were bored to larger diameters than authorized.

Frontinus did not respond by proposing new aqueducts. He responded by auditing what already existed.

His report to the emperor, De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae, is the earliest surviving official investigation of a water utility by a senior administrator. It is also a near-perfect articulation of the operational excellence philosophy that modern utilities still struggle to implement: systematic protocols, rigorous benchmarking, and accountable management deliver more value than new infrastructure alone.

Frontinus’s First Act: Map, Measure, Benchmark

When Frontinus took office, his first action was not to commission repairs. It was to commission information. He ordered comprehensive maps of the entire aqueduct system—something that had apparently never been systematically done—so he could assess conditions before making any operational decisions.

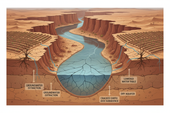

He then conducted what we would now recognize as a full water audit. For each of the nine aqueducts, Frontinus recorded the intake capacity, the measured discharge at key points along the route, and the volume actually delivered to the city. He documented the gap between what each aqueduct should have been carrying and what it actually was—identifying losses with a precision that would impress a modern IWA water balance practitioner.

For instance, on the Anio Vetus he found 4,398 quinariae at the intake but only 2,362 at the settling reservoir—a loss of 1,774 quinariae between source and distribution point. On other lines he discovered so-called “puncturers” who bored into pipes throughout the city, running secret branch lines to every business along the route so that only a trickle reached the public fountains.

He says that many had been neglected and were not working at their full capacity. He was especially concerned by diversion of the supply by unscrupulous farmers, tradesmen, and domestic users, among others.

— Summary of Frontinus, De Aquaeductu

The parallel to modern non-revenue water analysis is extraordinary. Frontinus was measuring real losses (physical leaks in conduits, siltation reducing flow capacity) and apparent losses (unauthorized connections, corrupt officials, pipe fraud) nearly two millennia before the International Water Association formalized these categories.

His findings revealed that the system’s problems were overwhelmingly operational, not structural. The aqueducts themselves were engineering marvels. The failure was in management: deferred maintenance, absent oversight, and institutional tolerance of theft. By enforcing existing regulations and restoring proper maintenance, Frontinus claimed to have practically doubled the effective water supply—without building a single new aqueduct.

The Modern Water Loss Crisis: Same Problem, Bigger Scale

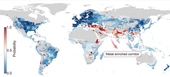

The scale of the modern non-revenue water crisis would have appalled even Frontinus.

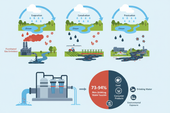

In developing countries, NRW levels frequently exceed 50%, meaning more than half of treated water never reaches consumers. Even in the United States, water main breaks are estimated to occur every two minutes across 2.2 million miles of distribution network. Nearly one in five gallons of treated drinking water is lost before it reaches customers or is improperly billed.

Frontinus would recognize this pattern immediately: massive investment in infrastructure itself, but chronic underinvestment in the operational systems that determine whether that infrastructure delivers consistent, accountable performance.

| Discipline | Rome, 97 AD (Frontinus) | Global Utilities, 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| System Auditing | Mapped all 9 aqueducts; measured intake vs. delivery at multiple checkpoints along each line. First known comprehensive water audit. | IWA water balance methodology exists but many utilities still lack validated audits. AWWA developed audit software because reliable data remains uncommon. |

| Real Losses | Underground leaks “difficult to locate and mend.” Siltation from river-fed aqueducts reduced flow. Mineral deposits roughened conduit walls. | 240,000+ US water main breaks/year. Aging infrastructure globally. Even slight surface roughening can reduce flow by up to 25%. |

| Apparent Losses | Fraus aquariorum: unauthorized connections, oversized pipes, bribery of officials. “Puncturers” boring secret branch lines throughout the city. | Meter inaccuracy, billing errors, illegal connections. In developing countries, apparent losses ~40% of NRW (World Bank estimate). |

| Maintenance Regime | Scheduled clearing of calcium deposits; tree-root exclusion zones; masonry inspections. 460-person dedicated crew. Winter maintenance windows. | Condition-based maintenance; pressure management. Chronic understaffing and aging workforce crisis in many jurisdictions. |

| Quality Management | Water categorized by source quality. Best for drinking, intermediate for baths, lowest for irrigation. Criticized mixing of sources and separated supplies. | Fit-for-purpose emerging: dual reticulation, water recycling, integrated resource planning. Still rare at scale. |

| Governance & Accountability | Published audit findings to emperor. Lead pipe stamps for traceability. Public warning that theft calculations were in hand. | Performance benchmarking (IBNET, IWA); S&P notes NRW affects credit quality. But many utilities lack transparency frameworks. |

| Result of Operational Reform | Effective supply “practically doubled” through management alone. Wards previously served by one aqueduct received water from several. | Best performers (Germany ~7%, Singapore <5%) achieve excellence through systematic operations, not exotic technology. |

Five Lessons from the First Water Commissioner

1. You Cannot Manage What You Have Not Measured

Frontinus’s insistence on mapping and measuring every aqueduct before making any operational decisions is the foundational principle of modern water utility management—and yet it remains surprisingly uncommon. In developing countries, validated water audits are rare. Even in developed nations, they are not systematically used. The AWWA developed water audit software specifically because many US utilities still lack accurate, validated data on their own losses.

Frontinus understood that without a complete picture of system performance, every decision is guesswork. His maps weren’t decorative—they were decision-support tools.

2. Operational Discipline Beats Capital Spending

The most striking finding in the entire De Aquaeductu is Frontinus’s claim that by enforcing existing maintenance standards, eliminating theft, and restoring proper operations, the effective water supply was practically doubled. No new aqueducts. No new engineering. Just competent, systematic management of existing assets.

This mirrors the E-Score Water thesis precisely: boring management beats heroic technology. Utilities with systematic operational protocols consistently achieve 15–20% water loss rates, compared to 30–40% or more in utilities that prioritize capital projects over operational frameworks. The ROI for operational excellence—estimated at 400–800%—dramatically exceeds the typical 50–200% ROI from capital infrastructure alone.

3. Theft and Apparent Losses Require Institutional Will

Frontinus documented an elaborate system of water theft: unauthorized connections, pipes bored to larger diameters than permitted, and outright bribery of aqueduct officials. He responded with meticulous recordkeeping and public accountability—using lead pipe stamps bearing the owner’s name to trace unauthorized connections and publishing his calculations as a warning.

Modern apparent losses are less colourful than Roman pipe fraud but equally damaging. Addressing them requires the same institutional courage Frontinus demonstrated: willingness to confront entrenched interests, political stakeholders, and organizational inertia. As one analysis of NRW noted, many utilities do not want to face the reality of being so inefficient—admitting to losing more than 50% of produced water is a psychological, professional, and political challenge.

4. Maintenance Is Not Optional—It Is the System

Frontinus treated maintenance as a core operational function, not an afterthought. He documented specific protocols: regular clearing of calcium carbonate deposits, exclusion zones around aqueducts to prevent tree-root damage, scheduled inspections of above-ground masonry. Two dedicated maintenance gangs—one state-owned (240 workers), one belonging to the emperor—were assigned to the system.

Archaeological evidence confirms these protocols worked. Researchers studying the Divona aqueduct in France found evidence of maintenance cycles at intervals of one to five years, conducted rapidly and never during summer—exactly as Frontinus advised. Modern hydraulic research confirms why: even slight roughening of conduit walls by mineral deposits can reduce flow rates by up to 25%.

5. Quality Differentiation Demands Operational Sophistication

One of the most sophisticated aspects of Frontinus’s management was his quality-based water allocation system. He categorized water from each aqueduct by source quality—spring, river, or lake—and directed it accordingly: the best for drinking, intermediate for baths and fountains, and lower quality for irrigation and flushing. He criticized the practice of mixing water from different sources and took steps to separate them.

This is effectively an early form of fit-for-purpose water management—a concept modern utilities are only beginning to implement at scale through dual reticulation systems, recycled water programs, and integrated water resource planning.

A 2,000-Year Timeline of the Same Problem

The E-Score Water Verdict

Frontinus’s De Aquaeductu is the original case study for the E-Score Water thesis. The operational disciplines he implemented—systematic auditing, loss quantification, maintenance protocols, quality differentiation, workforce accountability, and governance transparency—are the same disciplines that distinguish top-quartile utilities from the rest of the industry today.

The global water sector loses $39–50 billion annually to non-revenue water. That is not primarily a technology problem or an infrastructure problem. It is a management problem. And Frontinus told us how to solve it in 97 AD.

We just need to listen. And then we need to do the boring work.

The Deeper Lesson: Governance Before Technology

What makes Frontinus’s account so compelling for modern utility leaders is not the technical detail—it’s the governance philosophy. Frontinus was a senator, a former governor of Britain, a military commander. He brought to water management the same rigour he applied to military logistics: comprehensive intelligence, systematic planning, accountable execution, and transparent reporting.

His De Aquaeductu was simultaneously a technical manual, an administrative report, and a public statement of accountability. By publishing his findings and calculations, Frontinus created institutional transparency—making it clear that losses were being tracked, theft was being detected, and performance was being measured. He explicitly noted that his calculations served as a warning to potential thieves.

Too many modern utilities approach the problem backwards: investing in smart meters, SCADA systems, and AI-driven analytics while lacking the foundational governance structures—validated water audits, performance benchmarks, maintenance protocols, workforce accountability—that determine whether technology delivers value.

Technology without operational governance is Frontinus’s Rome before the audit: impressive infrastructure, chronic underperformance.

— E-Score Water

Singapore’s PUB, which has achieved water loss rates below 5%, operates with integrated water management that combines technology, public engagement, and rigorous policy. Germany maintains losses around 7% through well-maintained networks, proactive leak detection, continuous monitoring, and stringent regulatory standards. In both cases, the technology serves the governance framework—not the other way around.

Why Every Water Utility Leader Should Read This Book

The Aqueducts of Rome is short—roughly 12,750 words in the original Latin—and available in accessible English translations. It is not a difficult or academic read. But it is a profoundly useful one for anyone managing water infrastructure.

Frontinus demonstrates, with granular specificity, that the core challenges of water utility management have not fundamentally changed in two millennia. Leaks are still difficult to locate underground. Theft and unauthorized consumption still drain system capacity. Deferred maintenance still degrades performance invisibly. And institutional reluctance to prioritize operations over capital investment still produces systems that underperform their engineering potential.

The fact that Frontinus solved these problems—or at least dramatically reduced them—using nothing more sophisticated than maps, measurements, dedicated maintenance crews, and transparent reporting is both humbling and instructive. If a Roman administrator could double his system’s effective output through operational discipline alone, what excuse does a modern utility have for tolerating 20–50% non-revenue water?

The answer, as Frontinus knew, is not more aqueducts. It is better management of the ones we have.

“Boring management beats heroic technology.”

Frontinus proved it first. 97 AD. The evidence has only grown since.

Sources & Further Reading

- Frontinus, Sextus Julius. De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae. Translated by Charles E. Bennett, Loeb Classical Library, 1925.

- Rodgers, R.H. Sextus Iulius Frontinus: De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Deming, D. “The Aqueducts and Water Supply of Ancient Rome.” Groundwater, 2020. PMC 7004096.

- International Water Association (IWA). Water Balance and NRW Assessment Methodology.

- Liemberger, R. and Wyatt, A. “Quantifying the Global Non-Revenue Water Problem.” Water Science & Technology: Water Supply, 2019.

- World Bank. “The Challenge of Reducing Non-Revenue Water in Developing Countries.” WSS Sector Board Discussion Paper No. 8.

- AFD/Proparco. “Non-Revenue Water Is Water Wasted – Is Resource Wasted.” Global NRW cost estimated at $50B/year.

- Bluefield Research. “Water Losses Cost U.S. Utilities $6.4 Billion Annually.” April 2025.

- Aquatech. “Essential Guide: Leakage & Non-Revenue Water.” Germany ~7% loss rate; Singapore integrated model.

- Archaeological evidence of Roman aqueduct maintenance cycles: Divona (Cahors, France), showing 1–5 year intervals consistent with Frontinus’s advice.

- Hawle. “Non-Revenue Water in Distribution Systems: Facts & Figures.” IWA global loss data and European NRW ranges.